The conversation about non-stationary CDLs has become one of the loudest and most emotional debates that transportation has seen in recent years. Depending on where you get your information, HR 5688 is either a long-overdue fix for a broken system — or a Trojan horse that could reopen the very loopholes that drivers believe plagued the industry in the first place.

This tension is precisely the reason for the issue long distance.

From the episode’s opening moments, host Adam Wingfield clearly set the tone: It wasn’t about picking sides or telling drivers what to think. It was about hearing views directly, in full context, and letting listeners make up their own minds.

“My goal … is to get different perspectives and hear different sides of stories to formulate my own opinion,” Wingfield said. “Because at the end of the day, you can’t hear what other people are saying if you don’t listen.”

For this episode, that perspective came from OIDA Executive Vice President Levi Pugh—a former driver who has spent decades in the cab of a truck and in the halls of Washington.

What followed was neither a sweeping endorsement nor a defensive press tour. It’s a frank and sometimes uncomfortable discussion of how HR 5688 came to be, what it actually does, and the limitations — and risks — it may pose.

That’s what HR 5688 was designed to fix

At its core, Pugh explained, the main purpose behind non-stationary CDLs was operational, not ideological.

“The problem it was designed to solve was someone who lived in Florida going to Utah to work for a motor carrier … they could train there, test there and get their CDL, even if they weren’t a resident,” Pugh said.

This structure allowed large corporations and military programs to train drivers centrally, issue a CDL, and then have the driver repatriate it later. On paper, it solved the logistical bottleneck.

But as Pugh acknowledged, what lawmakers and regulators failed to predict was just how wide the doors would open.

“What we didn’t realize … was that we were opening the floodgates to allow not only people from other states, but other countries.”

He was clear about where the responsibility fell.

“There are a lot of unscrupulous driving schools out there… and these guys shouldn’t have been behind the wheel in the first place.”

This acknowledgment is important because it undermines the narrative that industry groups have recently gone blind. OIDA opposed the early expansion — sending cease-and-desist letters to more than 40 states that issued non-resident CDLs, Pugh said.

Key foods

- Future risk depends on interpretation, not volume

- The eligibility rules are practically the same

- No new access is created by HR 5688

- The main change is sustainability, not politics

- The authority of the secretary is present in both versions

The narrative of “driver shortage” under the microscope

As the conversation widened, Pugh returned again and again to what he described as the industry’s cardinal sin: legislating around a perpetual driver shortage narrative.

“For the last 40 years, we’ve been regulating and legislating the whole bull driver shortage narrative,” he said. We have no shortage of drivers. “We lack salaries, education and places to sleep.”

This framework shaped nearly every policy decision—including fast-tracking CDL access, easing training requirements, and dropout tolerance.

“We’re faster truck drivers, but we’re not faster than electricians, doctors or carpenters,” Pugh said. “Why don’t we want the guy carrying the load to really know what he’s doing?”

In his speech, non-tenured CDLs became another lever to keep seats filled rather than improving job quality—a decision whose downstream effects are now impossible to ignore.

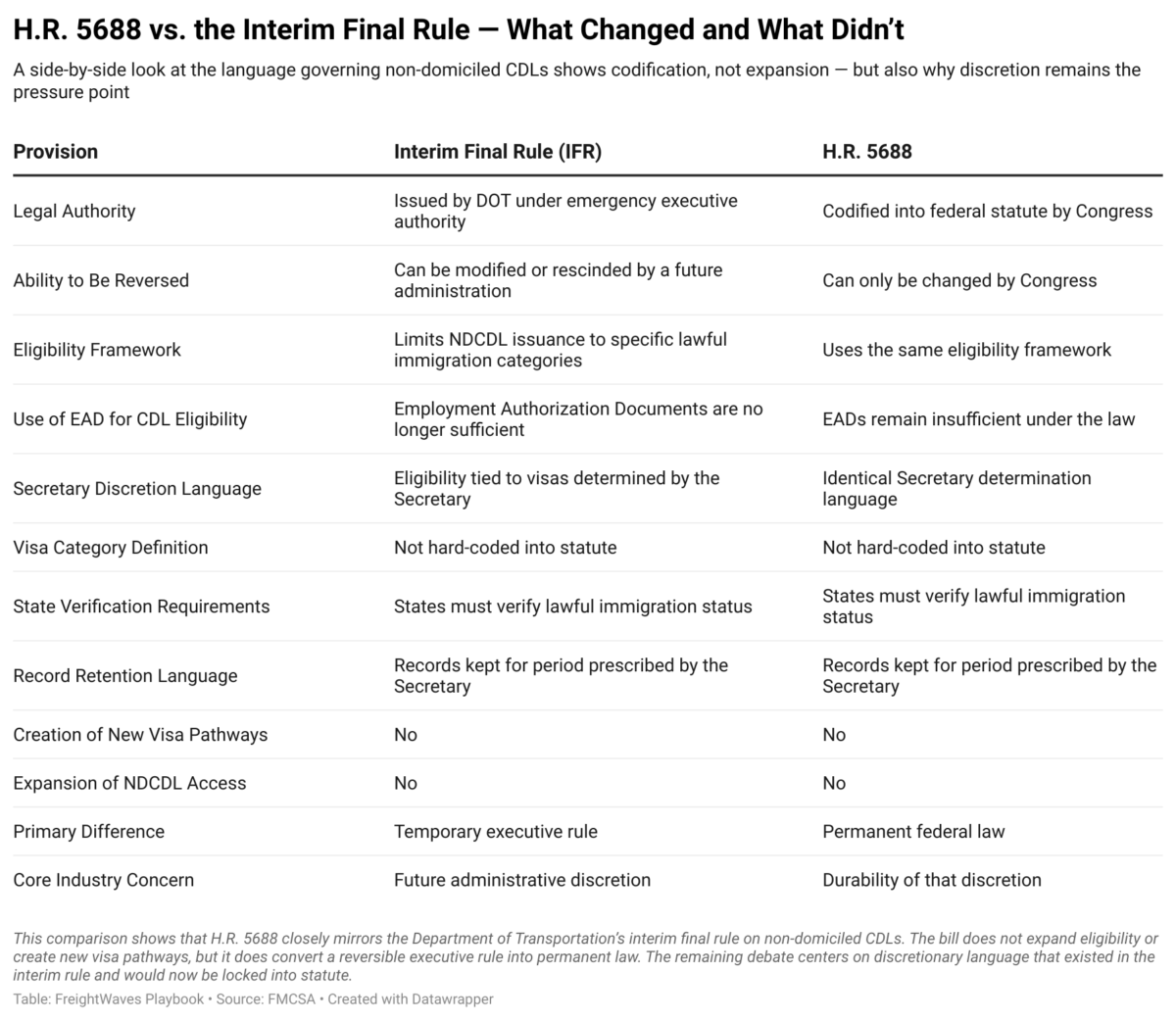

HR 5688 and the interim final rule

The turning point of the debate came when Wingfield pressed Pugh on the provision of HR 5688 – not its purpose.

Pugh’s main argument was simple: The bill would not expand access. It codifies existing restrictions previously issued through interim final rule issued by Secretary Sean Duffy.

“This bill is nothing more than an interim final rulemaking,” Pugh said. “It’s mirror language. That’s exactly what it is.”

And he argued that codification is crucial because agency rules can be overturned by the next administration with the stroke of a pen.

“If Congress passes this law … then Congress needs to change it.”

This explanation raised one concern—sustainability—but raised another.

Hole question

Wingfield didn’t let the conversation end there.

He read directly from the language of the bill, pointing to clauses that made eligibility based on visas “prescribed by the Minister” and record retention periods also “prescribed by the Minister.”

The concern was clear: today’s caution could turn into tomorrow’s vulnerability.

“Wouldn’t it be beneficial to amend the bill now so we eliminate the potential loopholes rather than revisiting this issue?” Wingfield asked.

Pugh did not dismiss the concern.

“I’d like to see no non-local CDLs. Period,” he said. “That would be great.”

But he framed HR 5688 as a choice between incomplete progress and a regulatory crackdown.

“If we don’t codify this … the next administration could completely scrap this law and go back to the Wild West.”

Pugh acknowledged uncertainty by emphasizing more about whether discretion itself creates risk.

“Anything can happen,” he said. “But before we get to that level, there are steps to be taken—manpower, visas, funding. It’s still better than what we have now.”

The exchange was one of the clearest moments of OIODA’s stance: supporting a bill it doesn’t like to avoid the results it fears most.

Why did the backlash hit?

Another recurring theme was the role of social media in fostering mistrust.

“Social media has become the new CB radio,” Pugh said. “Everyone has an opinion.”

Wingfield went further, noting that advocacy organizations are now judged not only by their policy outcomes, but also by the speed and clarity of their communication.

Pugh acknowledged that OIODA is slower than ideal to adapt — but emphasized the challenge of representing diverse members across generations.

“You have 20-year-old drivers and 70-year-old drivers. They receive information completely differently.”

This gap, he suggested, allowed simplistic narratives to fill the void—including the belief that OIODA supported non-resident CDLs.

“OOIDA does not support non-stationary CDLs. Period,” Pugh said. “We were the only ones who withdrew in 2019.”

Nuclear business

By the end of the episode, the disagreement turned into a question:

Is HR 5688 an incomplete protection — or a necessary line in the sand?

Pugh’s response was pragmatic, not triumphant.

“Is it great? No. Is it the best chance we have right now? Yes.”

He warned that refusing to participate, or poisoning the bill politically, could leave the industry with nothing.

“Something’s better than nothing – when there’s nothing to fall back on.”

Wingfield did not deny this fact. But he left listeners with an unresolved tension at the heart of the debate: whether settling now risks opening the door later.

What neither side discussed was this – the era of quiet politics is over. Social media has turned every bill into a public trial and every advocacy group into a defendant.

In that environment, clarity is more important than alignment.

And for truckers trying to make sense of HR 5688, the bottom line wasn’t who to trust — but the questions that still deserve answers.

The post Drafting a temporary law or being locked in ambiguity? The post Inside the Real Debate Over HR 5688 appeared first on FreightWaves.

(@atutruckers)

(@atutruckers)